The Shape of Design is Frank Chimero’s deeply intense, eloquently written, and passionate rumination that will elevate one’s appreciation of design from a practice to a craft.

It couldn’t have been a more fitting selection. What follows is a great discussion between a designer, a developer, and a product manager with varying degrees of appreciation for design.

I hope you enjoy the inaugural Books & Conversations as much as I have creating it.

![]()

Let’s begin with introductions. Tell everyone a bit about yourself, what you do, and what you care about.

![]()

Hi there! I’m Cat. I’m an information designer—which basically means I help people shape their ugly, awkward, and complicated content into something that is useful and appealing.

![]()

Hi all.

Firstly, John, thanks for organising this and kicking it off. Much appreciated!

I’m Beng-Fai. I’d probably classify myself as a tinkerer or ‘jack of all trades’—I do everything a modern understaffed Internet startup requires—write code, try to design, respond to support tickets, create PowerPoint decks, run spreadsheets, etc.

I’m really keen to learn from you all and to see how I can incorporate and bring some of this design thinking into my everyday work.

At many points I found myself near jumping up and down, shouting, “Yes! Exactly! That’s what I’ve been talking about!”

Cat

![]()

Now that we’re all acquainted, what was everyone’s overall impression of The Shape of Design?

![]()

Ah, that’s right. We are here to discuss the book…

Can I be honest?

If I hadn’t committed to reading it to participate in this conversation, I doubt I would have got past Chapter One.

At many points I found myself near jumping up and down, shouting, “Yes! Exactly! That’s what I’ve been talking about!”

But despite the arguments in the book giving me plenty to agree with (or think about), I wasn’t a huge fan of the way it was written.

Admittedly, the poetic style makes my humble profession sound a lot more serious and important than most of the population give it credit for. But for me it felt like it was taking what we do too seriously (even before saying this, I am already shooting holes in my own thoughts… why shouldn’t design be taken too seriously?!).

At the very least it made it hard for me to get back into it every time I picked it up.

![]()

Cat, I’m so glad you came out and said that. I’m probably in the same boat.

In principle, I liked some of the analogies (especially the ‘Kind of Blue’ jazz analogy for improvisation), but I found the style quite tough going and was tempted on many occasions to throw the towel in.

![]()

I’m secretly glad someone else felt the same way. I was half worried I’d be labelled and cast aside as a heretic! :-)

The improvisation section was easily my favourite section, and not just because I love Jazz!

It’s not that I hadn’t come across the idea of building upon another person’s idea with ‘yes, and…’ before, but the anecdote captured my imagination, and I just happened to be reading the chapter at a time when I could put the idea directly into use.

The other idea I have been thinking a lot about from the book is building frameworks. There is a great example in the book about a small child contributing to dinner by adding a pinch of salt to a meal. Salting is done one pinch at a time, so is controlled enough that you can trust a child to do it, but makes a big enough difference to the outcome that the child can see the output of what they’ve done.

I wouldn’t want to compare my clients to children, but I’ve been thinking that I need to do this more often in terms of seeking stakeholder feedback on projects.

I think there is a natural inclination for people to want to contribute to a project and sometimes when working on a project with many stakeholders, the feedback from the first couple of people can make huge positive differences to the project. But by the time you get to the last few people—because they still want to contribute in some way—they start picking apart minor details, such as the exact shade of blue you are using.

So one of my takeaways from reading the book is to develop a better framework for working with my clients, so that they can give me meaningful and effective feedback on projects. Maybe it’s as simple as guiding the form of feedback individuals or teams provide, i.e. Jane and Norman are going to provide feedback on style, while Thomas and Jack are going to provide feedback on the accuracy of content, etc.

![]()

It seems to me that despite the abstract style in which it was written, meditating on some of the ideas from this book can surface a lot of practical applications—as with Cat’s idea of building a framework for working with clients.

![]()

Absolutely!

Whether it’s jazz, or it’s cooking, [the book] really showed me that design thinking and its concepts apply to so many different fields.

Beng-Fai

![]()

Were there any other takeaways from the book that stood out for you? Are they likely to change the way you approach thinking about problems?

![]()

What about you John, what were your favourite takeaways?

![]()

This passage captures it all:

We have a tendency to toil and sweat the details, even beyond the point of clear financial benefit. David Chang, head chef at New York restaurant Momofuku, made a cameo on the television series Treme and framed the gap between efficiency and the extra effort extolled by so many creative individuals in their practice by calling it the ‘long, hard, stupid way’. In Chang’s case, the long, hard, stupid way was exhibited all over the kitchen, from preparing one’s own stock, to sweating out the details of the origins of the ingredients, to properly plating dishes before sending them out to the table. Commercial logic would suggest that Chang stop working once it no longer made monetary sense, but the creative practitioner feels the sway of pride in their craft. We are compelled to obsess. Every project is an opportunity to create something of consequence by digging deeper and going further, even if it makes life difficult for the one laboring.

The ‘long, hard, stupid way’ that Frank Chimero describes as the gap between efficiency and the extra effort that compels us to care so deeply about the work that we produce is something that is in constant tension for me. Much because it is often in direct opposition of other ideals that I also believe in such as Agile and Lean Startup Methodologies that extol doing the least amount of work possible to produce a result.

So the biggest takeaway for me was the reassurance that there’s still a place in the world for caring deeply about one’s work and obsessing over the details, sometimes to the point of being unproductive.

![]()

I second that!

My life is a constant battle between longing for efficiency and obsessing over the details.

![]()

Ok, just to put another point of view forward.

I completely get the notion of sweating and obsessing over the details, and taking real pride in your work. Having said that, I’m not sure it’s always practical.

In particular, I was somewhat miffed by these comments:

In Chang’s case, the long, hard, stupid way was exhibited all over the kitchen, from preparing one’s own stock, to sweating out the details of the origins of the ingredients, to properly plating dishes before sending them out to the table. Commercial logic would suggest that Chang stop working once it no longer made monetary sense, but the creative practitioner feels the sway of pride in their craft.

I’m going to offer a counterpoint:

- Which Michelin starred restaurant uses pre-made stock you can buy at the supermarket?

- Which Michelin starred restaurant is blasé about the source of their ingredients?

- Which Michelin starred restaurant makes their dishes look like inedible dribble before sending it to their diners?

I would argue that the ‘long, hard, stupid way’ is a prerequisite for fine dining. These things that may seem like a waste of time are expected by the diner when they pay that much for a meal—in some ways, it’s the minimum required to even get a seat at the table (excuse the pun).

I’m also going to go out on a limb here and suggest (without evidence) that it was because of his methodical methods Chang was a success, not despite.

But I’m ranting.

John, I completely agree with your point about the contrasting nature of Lean methods versus sweating the details. However, I think there’s a way for them to exist harmoniously.

Initially the Lean Startup methodology is, yes, scrappy. There’s a quote by Reid Hoffman that says, “if you are not embarrassed by the first version of your product, you’ve launched too late”. Kind of the opposite of the ‘long, hard, stupid way’. I don’t think there’s anything wrong with this approach. Yes, you can take an age and waste time sweating the details at this stage but that’s exactly what a startup doesn’t have—time.

But when you get to product-market fit and need to scale, the ‘long, hard, stupid way’ is probably the better way to go. Hopefully, you’re no longer as constrained by a lack of money and time and in a way, you know exactly what your customers want.

Any other comments on this take away?

As for my two cents, what I really liked about the book was Frank’s use of non-traditional design examples. Whether it’s jazz, or it’s cooking, it really showed me that design thinking and its concepts apply to so many different fields.

![]()

I would add that I don’t tend to think of the ‘long, hard, stupid way’ as a practical methodology so much as a biological instinct that is ingrained in anyone who approaches their work through the lens of craftsmanship.

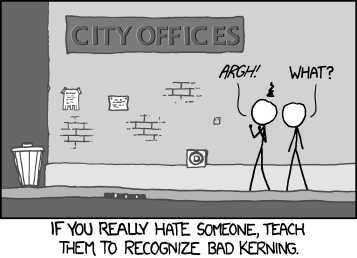

And that is where the tension lies for me. My compulsion to labour over code that is both efficiently expressive and aesthetically pleasing is not something that can simply be turned off. What’s more is that it has a tendency to transcend into everyday life in a way that is difficult to describe. Fortunately, there’s a great xkcd comic that uses kerning as an example to illustrate this perfectly:

Once you learn how to recognise poor kerning, the world becomes a frustrating wasteland of bad typography. For everyone else, ignorance is bliss.

I do agree that it’s possible for the ‘long, hard, stupid way’ to to exist harmoniously with Lean Startup methodologies, but I feel strongly that it isn’t simply a luxury to be afforded only in the absence of monetary and time constraints.

There’s an essay by Clayton M. Christensen that has had a particularly profound influence on the obligation to sweat the details in both my life and my work:

A voice in our head says, “Look, I know that as a general rule, most people shouldn’t do this. But in this particular extenuating circumstance, just this once, it’s OK.” The marginal cost of doing something wrong “just this once” always seems alluringly low. It suckers you in, and you don’t ever look at where that path ultimately is headed and at the full costs that the choice entails. Justification for infidelity and dishonesty in all their manifestations lies in the marginal cost economics of “just this once.”

[…]

The lesson I learned from this is that it’s easier to hold to your principles 100% of the time than it is to hold to them 98% of the time. If you give in to “just this once,” based on a marginal cost analysis, as some of my former classmates have done, you’ll regret where you end up. You’ve got to define for yourself what you stand for and draw the line in a safe place.

Clayton M. Christensen, How Will You Measure Your Life?

![]()

Frank Chimero talks a lot about narrative as an essential component to design. This isn’t anything new—we’re told about the importance of stories all the time, whether it is brands as stories or the use of user stories in software development and product management.

How do you feel about stories on a practical level? Do you frequently incorporate stories in some shape or form in your own work?

![]()

I’m always harping on at my clients about the importance of telling a good story about their product or service. But the book did prompt me to think more about how I tell the story of my work. The example Frank gives about working with design students to tell the story of shapes and colours on a page was quite interesting. It made me realise that it would probably help to talk that way when explaining design to clients. I know that I chose that colour or that type to induce some kind of feeling, but they don’t necessarily pick up on that without prompting.

![]()

Funnily enough, as a management consultant (previous life), whenever we were preparing a deck for a client (i.e. every day) we would often run through what our ‘story’ was before actually creating slides. If someone wanted to create a new slide, in addition to ensuring it adhered to good communication principles, we would often ask whether it fits in with the ‘story’.

Having said that, when you’re in the trenches, head down building stuff, I do find it hard to tie what I’m doing back to the overall story. I imagine it might be easier for a designer. The relationship between story and visuals appear to be easier to relate.

But this does bring another thought to mind. As alumni of the Rhode Island School of Design, the Airbnb founders’ design backgrounds were highly influential in the redesign of their website. So they mapped out story boards (like in a film or cartoon) of the user flow and made sure their work had an overarching story.

![]()

You both mentioned how difficult the book was to read at times.

How do you feel about the book now that we’ve had the time to give The Shape of Design some consideration? Would you recommend the book and if so, who should read it?

![]()

Hmmm… even though I found it hard to read, I think I would recommend it (with multiple warnings and caveats) to a select group of people. Namely, only people who are interested in creating stuff (and I deliberately use ‘stuff’ here).

![]()

Could you elaborate on what you mean by ‘stuff’?

![]()

Basically anyone who is creating something and is proud of what they’re creating—as a hobby or professionally. That list might include designers, developers, people who work in startups, painters, artists, musicians, etc.

![]()

Despite my personal preference for ‘plain’ writing, this is a beautiful book written in beautiful language and is definitely not out of place on my bookshelf.

My feeling is that it is the type of book that will be referenced more than read in it’s entirety. There are so many passages or quotes that can be used to prove points or prompt discussion.

I’d probably tell my friends or colleagues something along the lines of:

“If you don’t have time to sit down and slog through the entire book, then make sure you read a good review. Frank Chimero has a lot of great stuff to say!”

![]()

I think Cat says it much more eloquently than I. :)